The government’s Work Programme, whereby providers are paid on a results basis, is not fit for purpose and risks failing Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) claimants. Drawing on new research, Timothy Riley explains the problems with the funding model. In essence, getting the minimum performance benchmarks wrong creates a vicious circle of lower funding leading to lower performance, leading to still lower funding. He argues for a way forward that would cost no more than the government had planned.

The Work Programme is the government’s flagship national employment programme. It is substantially different from previous programmes, both in terms of its larger scale and the way it is commissioned. It is delivered by a range of (primarily private sector) providers who are largely paid on a payment by results basis, the results they are paid for being sustained periods in work for customers. The payment model differs for different groups of customers based in part on the benefits they claim, with job outcomes for customer groups considered to be further from the labour market being associated with larger payments.

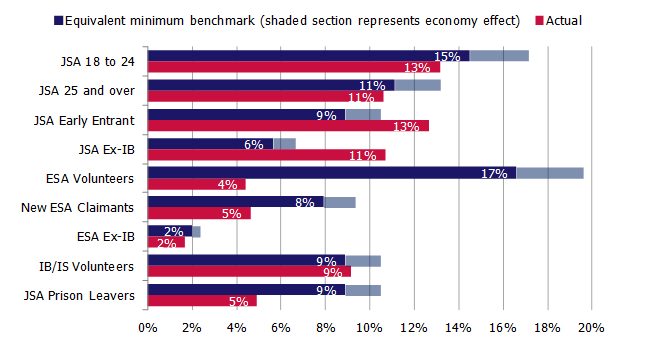

Unfortunately, recent performance data has shown that whilst the Work Programme is performing better for the main Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) payment groups, it is still well below the Department for Work and Pensions’ expected minimum performance levels for the Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) payment groups.

Figure 1: One-year job outcome measure – equivalent minimum benchmark compared to actual, by participant group (Jun 2011–Dec 2012 referrals)

Source: DWP: Information, Governance and Security Directorate; Inclusion calculations. Average weighted by monthly referral numbers.

The Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion recently published a new report, Making the Work Programme work for ESA claimants, which sets out the problems with the funding model for Employment and Support Allowance claimants and what could be done to fix it. The report is a part of a wider project called Fit for Purpose, supported by 22 organisations and looking at the future of employment support for people with health conditions and disabilities. The final report will be available in the summer.

Specifically, we argue that a toxic mix of a weak economy, lower than expected referrals to the programme, changes to the rules on who is referred, provider under-performance and setting the targets too high in the first place have combined to lead to big shortfalls in funding and support for those on the programme.

Our calculations suggest that around 11% of ESA claimants that are required to take part in the Work Programme would have achieved a ‘job outcome’ if the Work Programme had not been introduced. The DWP, however, set their estimate at 15%. These targets have been missed in every contract, and as a consequence – because the Work Programme is a ‘payment by results’ programme – funding to support ESA claimants has been substantially lower than anticipated.

Of course, you could see this as a policy success: performance has been below expectations but the DWP has not had to pay so much to providers – so the risk of failure has been successfully transferred away from tax payers. But this would be a pretty short-sighted view. The state still picks up the tab through the benefits bill, and lower funding means more people out of work for longer and receiving less support.

We argue that getting the minimum performance benchmarks wrong risks a vicious circle of lower funding leading to lower performance, leading to still lower funding. In a sense, this means that the funding model has been set up to fail – with lower outcome payments, and therefore lower funding overall, hard-wired into the contracts.

We estimate that the money available to providers to deliver services to ESA claimants (based on DWP spend on ESA customers) is likely to be about 40% lower than was originally planned, with DWP likely to spend on average £690 per ESA claimant compared to an estimated £1,170 when the programme was designed. And this is going to get worse: as of April 2014 there are no more ‘attachment payments’ paid to providers when customers join the Work Programme, meaning that at current performance the DWP will pay providers on average only £550 per participant – which needs to cover two years of support.

When these figures are grossed up for the whole programme, taking into account lower referral numbers as well as lower performance, we estimate that the government will invest less than half of what it intended to on supporting ESA customers through the Work Programme – with spending around £350 million compared to the £730 million expected.

In the event, we find evidence that Work Programme providers are actually spending a bit more than they receive from DWP on ESA participants, in order to maintain some levels of service. In effect they are cross-subsidising from outcome payments for Jobseeker’s Allowance participants. Whilst this may be helping to paper over the problems with the payment model, it is clearly neither satisfactory nor sustainable in the longer term.

Our report sets out an alternative model that we argue should be implemented for the remainder of the programme. This new funding model is based on four key assumptions:

- That spending should be restored for new participants to the same level as was originally intended – but foregoing the ‘savings’ that have already been banked by the Government;

- That in return for increasing funding we should expect increased performance;

- That the model should remain strongly outcome-based, so that risk is shared between the taxpayer and those providing services – in our proposal, around three quarters of funding would be linked to getting and sustaining jobs; and

- That funding should be highest for those that need the most support (and specifically, those who used to claim Incapacity Benefit).

Our proposed payment model is below.

Proposed Work Programme payment model for ESA claimants

|

PG5 – ESA Volunteer |

PG6 – ESA Flow |

PG7 – ESA ex-IB |

|

| Attachment payment |

£350 |

£350 |

£350 |

| Job entry payment |

£600 |

£900 |

£1,250 |

| Job outcome payment (three months in work) |

£1,150 |

£1,400 |

£4,000 |

| Maximum job sustainment payment* |

£2,300 |

£4,700 |

£9,620 |

| Cost per attachment |

£1,018 |

£1,181 |

£1,413 |

* Same overall levels as current model, but paid over 9 months after job outcome payment.

Without reform, in our view the funding model for the Work Programme is set up to fail ESA claimants, particularly those joining over the next two years. Whilst we and many others are rightly thinking about what should come next with ‘Work Programme Mark 2’, it is critically important that the Work Programme Mark 1 works for ESA claimants. Our report shows the failings of the current payment model for ESA groups, and a way forward that is achievable and would cost no more than the government had planned.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Homepage image credit: Grant Kwok

About the Author

Timothy Riley is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion. He specialises in research into labour market and skills policy, with recent projects including high profile evaluations of Lone Parent Obligations for the Department of Work and Pensions, and Want to Work for Jobcentre Plus, and has led Inclusion’s work on ethnic minority employment. @TimRiley83.

Timothy Riley is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion. He specialises in research into labour market and skills policy, with recent projects including high profile evaluations of Lone Parent Obligations for the Department of Work and Pensions, and Want to Work for Jobcentre Plus, and has led Inclusion’s work on ethnic minority employment. @TimRiley83.

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/archives/41681