Left Foot Forward

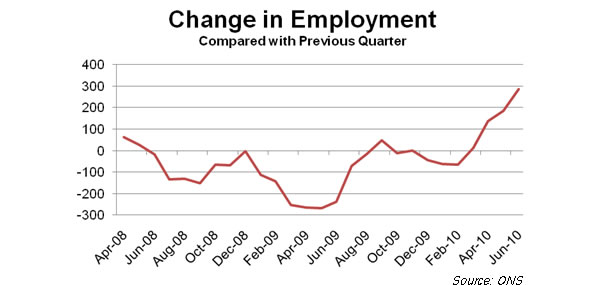

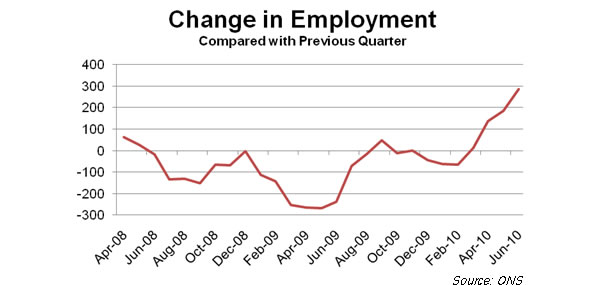

The ice we’re skating on is getting thinner; there’s much more good news than bad in today’semployment figures, but at the same time there are warning signs that the recovery was fragile evenbefore the coalition’s enthusiasm for cuts started to undermine confidence.

The key thing to remember when reading the labour market statistics is that they are a picture of the past; in today’s case, they’re show how things stood in early summer – May to July. The headlines in the Office for National Statistics’ press release compare these figures with the previous quarter (February to April) and that is what most newspaper stories concentrate on, but it is also useful to look at changes since last month’s figures (which covered April to June.)

These are the first statistics where practically the whole period is post-election, but of course, it is too early to say they show any effect of the new government’s policies. What stands out is the strong employment performance:

• There were 29,158,000 people in employment;

— This is 184,000 higher than the previous month,

— And 286,000 higher than the previous quarter.

• The employment rate was 70.7 per cent;

— This is 0.2 points up on last month,

— And 0.4 up on the quarter.

This performance was entirely due to a 308,000 quarterly increase in private sector employment. Public sector employment was down 39,000 on the month and 22,000 on the quarter, a figure confirmed in separate figures for public sector employment released today. Employment was down in central government, local government, the civil service – every sector except education and public corporations (which includes the nationalised banks).

Over half the increase compared with the previous quarter is accounted for by a 166,000 rise in part-time employment, but full-time employment rose by 121,000 on the quarter, 44,000 compared with last month. Temporary employment is up on the quarter (+74,000) but slightly down compared with last month (by 3,000).

One point worth noting is that men’s employment, which suffered more than women’s in the initial phase of the recession, has been increasing more in recent months:

The unemployment figures also looked reasonably good. The Labour Force Survey measure (based on asking people if they don’t have a job, are looking for one and can start work at short notice) shows unemployment at 2,467,000. This is up 10,000 on last month’s figure (though the rate is unchanged at 7.8 per cent) but down 8,000 on the quarter (and the rate is down 0.1 points).

So far the economy has done quite well on this front – eighteen months ago I thought we would have reached 3 million unemployed by now, but so far we have (just) avoided going over the 2.5m mark. Compared with the last recession, the unemployment performance looks even better:

One driver of the good news on unemployment is the decline in redundancies. In May – July this year there were 142,000 redundancies, 10,000 fewer than in April – June, 31,000 fewer than in Feb – April and 91,000 fewer than in May to July 2009. The number of redundancies is down in every industrial category except public administration, health and education and the redundancy rate (the number of redundancies per thousand workers) is down from 9.3 a year ago to 5.8 in the latest figures.

The picture for vacancies, while not quite as cheery as this is still pretty good:

|

|

|

|

No. of vacancies |

No. of unemployed people per vacancy |

|

|

|

| May/Jul 2009 |

429,000 |

5.8 |

| Feb/Apr 2010 |

472,000 |

5.2 |

| Apr/Jun 2010 |

490,000 |

5.0 |

| May/Jul 2010 |

481,000 |

5.1 |

On inactivity there is good news as well, with the number of economically inactive working age people down 88,000 compared with last month and 158,000 compared with the previous quarter. The results are more mixed for the number of economically inactive people who say they want a job, however, with a fall of 28,000 on the quarter but an increase of 23,000 from last month’s figures. This is an important figure, because it is as close as we get to a statistic for hidden unemployment and if we add it to the number unemployed we get a “want work” level of 4,829,000: up 33,000 on the previous month, but down 36,000 on the quarter.

Overall, these are quite encouraging results and Yvette Cooper could reasonably claim to have handed over a labour market that was starting to reflect the GDP recovery and in better shape than it had been at the same stage of the 1990s recession. But there are signs of fragility. First of all, notice that the comparison with the previous quarter looks better than with the previous month, especially the unemployment and “want work” levels.

Secondly, the figures for the “claimant count” measure of unemployment are not as good. For most purposes the claimant count (the numbers claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance) isn’t as useful as the LFS measure – JSA is such a lousy benefit there are plenty of genuinely unemployed people who don’t qualify. But it does have the advantage of being more up to date, with the most recent figure being for August when the figure rose for the second month in succession:

|

|

|

Claimant count (to 5 s.f.) |

|

|

| June 2010 |

1,460,100 |

| July 2010 |

1,461,200 |

| August 2010 |

1,466,300 |

Third up, there’s been an increase in short-term unemployment. During a recovery you would expect to see short-term unemployment (under 6 months) coming down before the number for longer durations. As fewer people come on to the register, and previous cohorts either get jobs or move into long-term unemployment this should be the first sign of an improving labour market – and indeed, this is what happened last year and at the start of this year. But this month’s figure of 1,186,00 is 27,000 higher than last month and 14,000 higher than the previous quarter. This could just be a blip, but it does worry me.

Then there’s been an increase in unemployment amongst 18 – 24 year olds. This age group tends to be first out and last in to jobs, so the 4,000 increase on last month and 16,000 increase on the quarter could be another rumble on the horizon.

Finally there’s the problem of involuntary part-time and temporary work. The improved employment figures haven’t led to a reduction in the number of people who are only doing ‘atypical’ jobs because they couldn’t find a permanent full-time job – the level and the rate are still rising:

|

|

|

|

|

|

People in involuntary

temp jobs (to 3 s.f.) |

% |

People in involuntary

p/t jobs (to 4 s.f.) |

% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Feb/Apr 2010 |

537,000 |

35.8% |

1,083,000 |

14.2% |

| Apr/Jun 2010 |

565,000 |

35.9% |

1,079,000 |

14.1% |

| May/Jul 2010 |

569,000 |

36.1% |

1,116,000 |

14.4% |

Taken together, these figures would be very encouraging if we were looking at them confident that policies to sustain the recovery were in place. But they do not indicate a labour market that’s strong enough for us to claim that growth is self-sustaining. The fact that the comparison with three months ago is stronger than with last month could even be a hint that we were already heading into stormy waters before the cuts began.

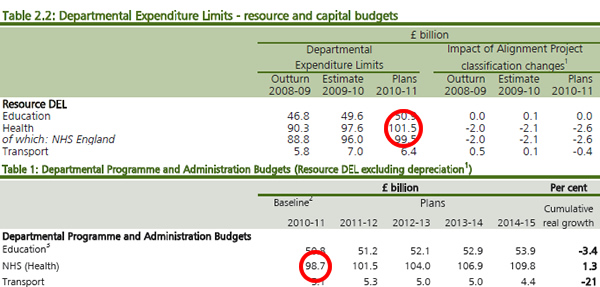

Table 2.2 of the June Budget clearly shows that the departmental expenditure limit for current spending in the Department of Health would be £101.5 billion. But Table 1 of today’s Comprehensive Spending Review sets out that the same number is £98.7 billion.

Table 2.2 of the June Budget clearly shows that the departmental expenditure limit for current spending in the Department of Health would be £101.5 billion. But Table 1 of today’s Comprehensive Spending Review sets out that the same number is £98.7 billion.