A miserable little compromise: Why the Liberal Democrats have suffered in coalition.

Tag: coalition

LSE British Politicast Episode 2: Austerity Economics and Central Banking

LSE British Politicast Episode 2: Austerity Economics and Central Banking

Posted: 31 Jul 2013 04:00 AM PDT

In this episode, we focus on austerity economics and the role of central banks in times of financial crisis. The UK coalition government embarked on a programme of spending cuts when it came to power in 2010. Since then many economists and academics have argued that the intellectual justification for austerity has crumbled and it is a self-defeating strategy in bad economic times. Mark Blyth, Professor of Political Science at Brown University in the US, takes this view in his new book Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. He discusses why he thinks austerity is merely a form of self-harm. We also hear from Claire Jones, economics reporter at the Financial Times about the role of central banks, particularly that of the Bank of England, in the age of austerity.LSE British Politicast Episode 2: Austerity Economics and Central Banking.

Conservative claims about benefits are not just spin, they’re making it up

Government ministers like Iain Duncan Smith and Grant Shapps are misrepresenting official statistics for political gain

Declan Gaffney and Jonathan Portes

guardian.co.uk, Monday 15 April 2013 15.32 BST

Conservative minister Grant Shapps has quoted a misleading statistic about the number of people on incapacity benefit dropping their claims as evidence of a broken welfare system. Photograph: Richard Sellers/Allstar/Sportsphoto Ltd

In the past three weeks, readers of mainstream UK newspapers have learned a number of things about the UK social security system and those who rely on it. They have learned that 878,000 claimants have left employment and support allowance (ESA) to avoid a tough new medical assessment; that thousands have rushed to make claims for disability living allowance (DLA) before a new, more rigorous, assessment is put in place; and that one in four of those set to be affected by the government’s benefit cap have moved into work in response to the policy. These stories have a number of things in common. Each is based on an official statistic. Each tells us about how claimants have responded to welfare policy changes. Each includes a statement from a member of the government. And each is demonstrably inaccurate.

When we say inaccurate, we are choosing our words carefully. Politicians are inevitably selective in the data they choose to publicise, picking the figures that best suit whatever story they want to tell. This can mean that stories that are technically accurate can nonetheless be potentially misleading. Within reasonable limits that is in itself neither improper nor unethical: indeed, it is virtually unavoidable. But here are some examples that are not just misleading: they assert that official government statistics say things they do not.

First, the claim that “more than a third [878,000] of people who were on incapacity benefit [who] dropped their claims rather than complete a medical assessment, according to government figures. A massive 878,300 chose not to be checked for their fitness to work [our italics].” For the Conservative party chairman, Grant Shapps, the figures “demonstrate how the welfare system was broken under Labour and why our reforms are so important”.

In fact, every month, of the roughly 43,000 people who leave ESA, about 20,000 have not yet undergone a work capability assessment (WCA); a number that over four years or so adds up to the headline 878,000. There is no mystery about this: there is an inevitable gap between applying for the benefit and undertaking the WCA. During that time, many people will see an improvement in their condition and/or will return to work (whether or not their condition improves). DWP research has shown that overwhelmingly these factors explain why people drop their claims before the WCA; it also showed that it was extremely rare for claimants not to attend a WCA. In stating, in effect, that official figures showed the opposite of this, the story was simply wrong.

Iain Duncan Smith’s assertion about a surge in DLA claims turns on the fact that DLA is being abolished for new claims and replaced with a new benefit, personal independence payment (PIP), for which most claimants will require a face-to-face assessment (for DLA, other forms of medical evidence could be used to support claims). He said: “We’ve seen a rise [in claims] in the run-up to PIP. And you know why? They know PIP has a health check. They want to get in early, get ahead of it. It’s a case of ‘get your claim in early’.”

Some very specific figures were cited: “In the north-east of England, where reforms to disability benefits are being introduced, there was an increase of 2,600 in claims over the last year, up from 1,700 the year before, the minister told the Daily Mail. In the north-west, there were 4,100 claims for the benefits over the past 12 months, more than double the 1,800 in the previous year, he said.”

But these figures, to be found on DWP’s website, in fact represent the change – successful new claims minus those leaving the benefit – in the total DLA caseload from August 2011 to August 2012, crucially including pensioners and children who are not affected by the change from DLA to PIP. They do not constitute even indicative evidence of a DLA “closing down sale”. So what happens if we look at new claims, or indeed the total caseload, for those (between 16 and 64) who will be actually affected by the change? In fact, both fell, in both regions, between those two dates. These falls – well within the normal quarterly variation – tell us little, except to show conclusively that Duncan Smith’s statements are supported by no evidence that he has offered whatsoever.

Finally, the coalition’s flagship “benefit cap”. On this occasion, not only did Duncan Smith misrepresent what his own department’s statistics meant, but he chose to directly contradict his own statisticians, claiming: “Already we’ve seen 8,000 people who would have been affected by the cap move into jobs. This clearly demonstrates that the cap is having the desired impact.”

But the official DWP analysis, from which the 8,000 figure is drawn, not only does not say this, it says the direct opposite: “The figures for those claimants moving into work cover all of those who were identified as potentially being affected by the benefit cap who entered work. It is not intended to show the additional numbers entering work as a direct result of the contact [their emphasis].”

As DWP analysts know only too well, people move off benefits into work all the time. Unless it is shown that these flows have increased for those affected, and by more for them than for other claimants – and no such analysis has yet been published, either by DWP or anybody else – we know nothing about whether the policy has had any impact (this claim is now being reviewed by the UK statistics authority).

None of this should be taken as comment on the merits of the policies in question. But these misrepresentations of official statistics cross a line between legitimate “spin”, where a government selects the data that best supports its case, and outright inaccuracy.

Public cynicism about official statistics is often misplaced – the UK, like most democracies, strictly limits the ability of governments to influence the production and dissemination of official data, often, no doubt, to the frustration of ministers. These restrictions on what government can do with official data are an unsung but essential element in modern democratic governance. When government seeks to get around these limitations by, in effect, simply making things up, this is not just an issue for geeks, wonks and pedants – it’s an issue for everyone.

• This article was amended on 19 April 2013. The original said 130,000 people leave employment and support allowance every month; that is in fact how many people leave ESA each quarter.

Measuring Leviathan: Big Government and the Myths of Public Spending | Whitehall Watch

Posted on January 14, 2013 by Colin Talbot

The political debate about public spending in the UK is bedevilled by myths and spin about how much we actually spend. So I thought it was time for a little myth-busting primer, with some pretty diagrams, about how we should be discussing public spending….

There are three main ways of measuring public spending, each of which has advantages and disadvantages.

Nominal (Cash) Spending

The first is in what is technically called the “nominal” amount spent – that is in actual cash that goes out of the Treasury coffers. Because of the effects of inflation, this nearly always rises (see Figure 1). Only twice in the past half century has the cash amount fallen – in 2000-01. It is forecast to fall again, for one year only, in 2012-13.

This is useful to some who want to argue that the State spends too much – for example some right-wing Conservative politicians and think-tanks currently claim that we are not experiencing “cuts” because the actual amount of cash being spent by the government continues to rise. Figure 1 makes it look like the State is an ever-increasing devourer of resources. But if inflation in prices is taken into account, things look a bit different.

Figure 1 Public Spending in ‘nominal (cash) terms 1965-66 to 20214-15 (£ billion)

Source: based on HM Treasury[i]

Real-Terms Spending

Real-terms spending is the amount spent with inflation taken into account.

Figure 2 Public Spending in Real-Terms (2011-12 prices)(£ billion)

Real-terms spending shows a far less dramatic increase than nominal spending, and some periods where spending levelled-off or even decreased. It shows, for example, a significant (mainly forecast) decrease in real-terms under the current Coalition government.

Again though, this way of looking at public spending can make it look like the State is a more-or-less ever expanding beast soaking up more and more of the nation’s wealth. This may, or may not be true – but the only real way of knowing is by seeing how public spending compares to nations wealth.

Spending as a proportion of GDP

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the main measure used by governments and others to estimate how wealthy countries are. There are many criticisms of GDP measurement, which we won’t go into here, but it’s the best we have at the moment for tracking growth (or lack of it) in our won economy and comparing our economic performance with other countries.

Public spending as a proportion of GDP has thus become the main, and most useful, way of tracking how much our national wealth we devote to public activities as opposed to private enterprise.

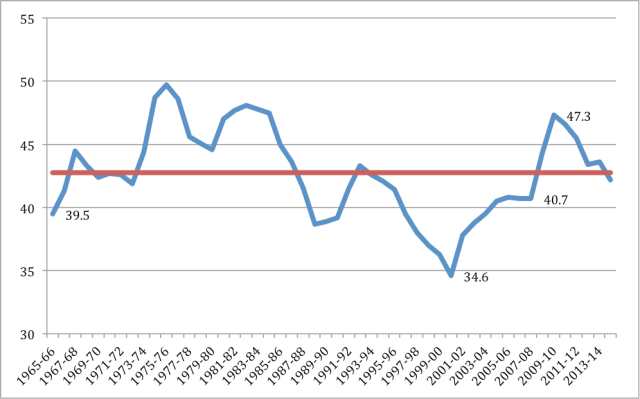

It’s main fault is obvious: because it is a ration of public spending and GDP a sudden change in GDP can easily look like a sudden change in public spending. Thus, for example, it looks like public spending suddenly sky-rocketed in the last three years of the last Labour government (see Figure 3) – whereas in fact (in real-terms – see Figure 2) it only increased slightly. The sudden change from 40.7% of GDP to 47.3% was almost entirely due to the recession the UK experienced as a result of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Figure 3 Public Spending as a percentage of GDP (1965-66 to 2014-15)

Public spending as a proportion of GDP has averaged just under 43% of GDP (42.76% to be more precise) for the past 50 years.

It has swung between as high as 50% (under Labour 1975-76) and as low as 35% (also under Labour in 2000-01).

But what a detailed analysis of these figures shows is that some of mythology that passes for political “facts” in Britain is just that – myth.

The first is that Labour is always the “tax and spend” Party whereas the Conservatives are far more thrifty with the public’s money.

The facts are rather more mixed (see Figure 4). It is true that the 74-79 Labour Government spent on average more, as a proportion of GDP, than any other government in the past 50 years – but this is not true for the other periods of Labour government, when Labour spent less, on average, than the Conservative (or Conservative led) governments.

In particular the widespread myth that the last “New” Labour government spent vastly more is just that – a myth. On average, even including the effects of the GFC, the last Labour government spent the least of the Governments since 1965. The myth has grown up because both Labour and their opponents wanted to promote the idea Labour spent lots. And because, especially between 2000 and 2005, Labour did rapidly increase spending – especially on health and education – but only after a period of unprecedented low spending between 1997 and 2000.

Figure 4 Public spending as percentage of GDP under different Governments (1965-2015)

This analysis only covers one aspect of public finances – spending – which is itself only one measure of how big the State is. But I hope it will help people to explain, and explore, some of the real issues about public spending rather than trading in myths and spin.

[i] All the figures used in this analysis are based on Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis (PESA), published annually by HM Treasury. The figures for 1971-72 to 2014-15 are taken from PESA 2012. For 1965-66 to 1970-71 are taken from PESA 2003. Some of the calculations are my own, based on the HMT figures.

via Measuring Leviathan: Big Government and the Myths of Public Spending | Whitehall Watch.

Someone tell David Cameron that tax avoidance starts at home

Cameron’s Davos speech was long overdue. But the very corporate tactics he condemns abroad, he enables in the UK

Richard Murphy

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 24 January 2013 14.40 GMT

After a decade of campaigning for tax justice it was gratifying to hear David Cameron endorse much of what we have called for at Davos this morning. Unfortunately, as just a few examples show, the prime minister has a long way to go before he walks the talk.

Tax avoidance

Cameron’s said “There are some forms of avoidance that have become so aggressive that …. it’s time to call for more responsibility and for governments to act accordingly.”

When delivering the message he added: “Companies need to wake up and smell the coffee, because the customers who buy from them have had enough”. It could not have been more obvious that he has Starbucks in mind. He’s set the bar on this issue at a point where it must be tackled.

And yet Cameron faces a massive domestic credibility problem as a result. The government’s much trumpeted General Anti-Abuse Rule, which will be enacted this year, which Cameron says targets tax avoidance, will deliberately not go near targeting the sorts of tax avoidance undertaken by Starbucks, Google and Amazon. Legislation put forward by Michael Meacher MP and written by me that would let HM Revenue & Customs challenge their sort of tax avoidance has also been rejected by the government.

It’s all very well for Cameron to say that tax avoidance must be tackled internationally. His difficulty is that he could do it at home as well and has chosen not to do so. He’s correctly assessed that there is real political anger on this issue now; he’s got his assessment of what people want seriously wrong if he thinks his government’s proposals will satisfy those demanding reform.

Transparency

Cameron said: “The third big push of our agenda is on transparency, shining a light on company ownership, land ownership and where money flows from and to.” I’m delighted he said this, but I am disappointed he added that “this is critical to developing countries” as if somehow this is a problem for Africa but not for us.

Opacity permits corruption everywhere. Accounts that fail to account meaningfully hinder effective economic decision-making. Limited liability companies, existing in a void with no apparent owners who accept responsibility for their decisions, blight economies and permit massive tax dodging. And nowhere is that more true than in the UK.

At present a multinational company trading in the UK does not have to publish a separate profit and loss account for this country so we can see how much tax it pays in the UK. Nor does it have to do so for all the tax havens in which it operates. If Google, Starbucks and Amazon had been required to do that we’d have seen their tax avoidance a lot earlier. So yes, we need transparency for developing countries, but we need it too in the form of full country-by-country reporting.

Despite that, just a couple of days ago David Gauke, the Conservative exchequer secretary, under Labour questioning showed his continued indifference towards country-by-country reporting.

That’s also true on beneficial ownership. There is no legal requirement to disclose beneficial ownership of a company in the UK at present, and our company registry is a near perfect example of appalling company regulation on this and other issues, striking off hundreds of thousands of companies a year rather than demand that they comply with their legal obligations.

If Cameron wants to show the world the way on beneficial ownership he can begin at home by making Companies House into a regime fit for the 21st century. He should follow up with the land registry – riddled as it is with anonymous offshore companies – and then demand that our tax havens put beneficial ownership on public record just as we should.

Automatic information exchange

Cameron said: “If there are options for more multilateral deals on automatic information exchange to catch tax evaders, we need to explore them.” I agree, wholeheartedly. It’s just a shame he said this the month the UK’s appalling tax agreement with Switzerland comes into force that guarantees tax evaders anonymity, lets them off most of the tax they owe, and preserves Swiss banking secrecy in the process. Germany’s parliament rejected such a deal to hold out for full automatic information exchange with Switzerland. The UK harmed the cause by going ahead alone.

And that’s the problem with this whole speech. The talk is great. I welcome it. As Cameron said: “After years of [tax] abuse, people across the planet are calling for more action and most importantly, there is gathering political will to actually do something about it.” He’s right. But Cameron’s pretending the solution lies outside the UK. It doesn’t. It starts at home. And some of the biggest obstacles to be overcome require some serious rethinking of his own government’s agenda on tax, accountancy, regulation, transparency and tax havens, all of which could change without the need for any outside co-operation. We’ve still got a long way to go to win this debate.