By Prem Sikka

The British state has declared war on low and middle income families

Perhaps, there was a time when governments declared war on poverty. After all, no economy can flourish whilst masses are in poverty and can’t buy the goods and services produced by businesses. Now, the British state has declared war on low and middle income families.

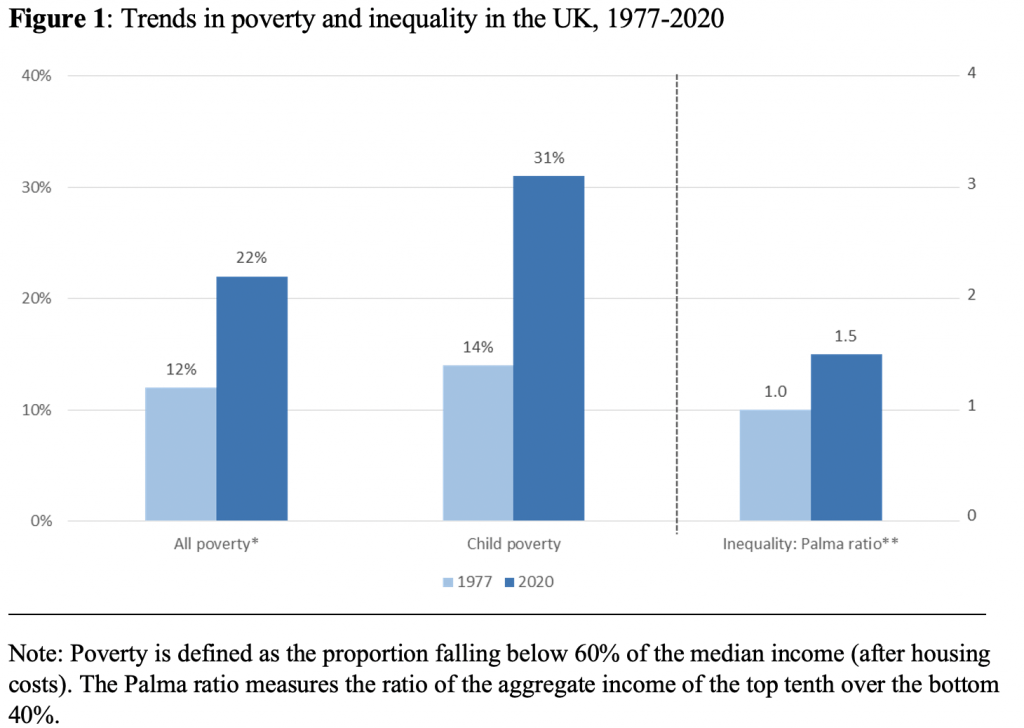

The squeeze on workers has reduced their share of the gross domestic product (GDP), in the form of wages and salaries, from 65.1% in 1976 to around 50% at the end of second quarter of 2023. Between1980 and 2014, real GDP growth averaged around 2.2% per year and the economy has grown sporadically since then. However, most people have seen little benefit of that growth.

One study estimates that “if wages had continued to grow as they were before the financial crash of 2008, real average weekly earnings would be around £11,000 per year higher than they currently are – a 37 per cent lost wages gap”. The real average earnings are unchanged since 2005.

With tax perks and little or no curbs on corporate profiteering, dividends and executive pay, the wealthiest 10% of households hold 43% of all the wealth; in comparison the bottom 50% have only 9%. Just 50 families have more wealth than half of the population, comprising 33.5m people. They fund political parties and buy influence to ensure that their privileges remain unchecked.

Hardly any institution of government cares about rising inequalities and their consequences. The median annual FTSE100 CEO pay has rocketed to around £3.91m, equivalent to the pay of 118 [London] workers. In September 2023 median monthly UK wage was £2.264, or £27,168 a year. There are regional variations. For example, the median wage in Leicester is £1,923 a month, equivalent to £23,076 a year, compared to £2,706 a month or £32,472 a year in London. In the late 1970s, a multiple of four times the average wage enabled people to buy a modest house. The average house price now is around £290,000 in the UK, £720,000 in London, £485,000 in South East England and £265,000 in Leicester. Most people can’t buy a home and for the rest of their life will pay rents to swell profits of landlords.

Work does not pay enough. Around 38% of the people topping-up their incomes through Universal Credit (UC) are in employment. Low and middle income families face the grim choice of eating or heating and rely upon around 2,600 food banks. In 2022, almost 11,000 people in England were hospitalised with malnutrition. Scurvy and rickets have returned. Each year, around 93,000 people, including 68,000 retirees die from poverty.

The poor are being killed through politics of neglect. Due to lack of investment, staffing and planning 65% of maternity care in England is unsafe. The number of people waiting for hospital appointment in England has increased from 2.5 in 2010 to 7.78m at the end of August 2023. Almost a million patients have turned to private healthcare, but millions can’t afford to do that. In the last five years, 1.5m have died whilst waiting for a hospital appointment. Some 2.6m have become chronically ill and are unfit to work. Rather than alleviating poverty and improving healthcare, the government wants to force the sick and disabled to work by cutting their benefits to enable it to cut taxes for the wealthy. The UK has one of the lowest life expectancies among rich countries.

The war on the poor has been normalised. In March 2020, Covid lockdown jeopardised corporate profits. The government increased Universal Credit payments to the poorest by £20 a week. However, once that threat receded the £20 uplift was withdrawn. Instead, the government handed £10 subsidy to enable the well-off to eat at restaurants under its Eat Out to Help Out Scheme at a cost of £849m to the public purse. Prime Minister Sunak boasted that he was very good at taking money away from the poorest and handing it to the rich.

Social security support is abysmal. Statutory Sick Pay of £109.40 per week is the lowest amongst OECD countries. Former Prime Minister Boris Johnson complained that he could not live on his £157,000 salary. Conservative MP Peter Bottomley complained that living on MP salary (currently £87,000 a year) is ‘really grim’. Former chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng and former health secretary Matt Hancock demand £10,000 a day in consultancy fees. But they expect people to live on £109.40 per week.

Redistribution of income and wealth is off the political agenda and Labour and Conservative parties compete to see who can squeeze the poorest the hardest. Examples include the two-child benefit cap, first introduced in 2017, which affects 14% of all children and deprives their families of £3,000 a year. Just £1.3bn a year would lift 250,000 children out of poverty, and a further 850,000 would be in less deep poverty. £400m could provide free meals for all school children to reduce hunger and remove the stigma of poverty, but parties are against it.

The welfare of corporations and the rich is central to state policy and neither the Conservatives nor the leadership of the Labour Party want to change it. Labour is promising ‘ironclad discipline’ with public finances which means real cuts in public services and wages of public sector workers. There is virtually no political opposition to welfare of the rich. The government found £1,162bn of cash and guarantees to bailout banks. £895bn of quantitative easing was handed to speculators. Each year billions are handed in subsidies each to rail, auto, oil, gas, steel, broadband and other companies. Both parties have ruled out wealth taxes, increasing capital gains tax or ending tax perks for the richest. None of this is accompanied by any assessment of the impact on the lives of the less well-off.

The war on the poor cannot provide economic or social stability. It has destroyed lives and inhibited social development. The institutions of government need to listen to saner voices, trade unions and non-governmental organisations to build a fair and just society through redistribution, higher public investment and by freeing themselves from the shackles of neoliberal economics.

Prem Sikka is an Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of Essex and the University of Sheffield, a Labour member of the House of Lords, and Contributing Editor at Left Foot Forward.